How ‘direct financial loss’ was converted into ‘lost opportunities’.

If you suffer from insomnia you may find that ploughing through a PHSO investigation report will have you nodding off in no time. They are repetitious and dull but if you can stay the course they reveal all that is wrong with our current system of holding government bodies to account.

On 21 March 2024, the long-awaited report into ‘Women’s State Pension Age’ was released. 96 pages setting out PHSO’s findings of injustice and remedy. Part one of this report was issued in July 2021 which found maladministration on the part of DWP in relation to delays in notification of changes to pension age for women following the 1995 Act. This report managed to reduce the delay from 15 years to just 28 months but was not challenged at the time by Waspi campaigners and indeed was celebrated as an important first step in the recognition of harm.

When it comes to deciding remedy, PHSO determines whether the identified maladministration led to harm or ‘injustice’. This is confirmed at point 259 in the final report.

259. Our published Service Model Guidance says when considering injustice, ‘the key question is “did the injustice claimed occur in consequence of the maladministration/service failure we have found?” We consider what would have happened and whether someone would have been in a different position if the maladministration had not occurred.

The severity of injustice had already been reduced in the first report by the determination that until 2004 the DWP had acted appropriately in finding ways to disseminate information regarding changes to pension age.

169. Between 1995 and 2004, accurate information about changes to State Pension age was publicly available in leaflets, through DWP’s pensions education campaigns, through DWP’s agencies and on its website. What DWP did reflects expectations set out in the Civil Service Code, the DWP Policy Statement, the Pension Service’s Customer Charter and the Benefits Agency Customer Charter.

In the final report, the focus was on redefining ‘direct financial loss’ into ‘lost opportunities’.

342 When considering claims of financial loss, we need to distinguish between any financial losses or hardship complainants may have experienced because their State Pension age changed, and any losses resulting from maladministration in DWP’s communication about those changes. As we have explained, we cannot consider the impact of changes in the law about State Pension age.

343. Some sample complainants told us they have suffered financial loss because their State Pension age changed. For example, Ms U said she has suffered financial loss of £39,000, ‘being the amount I would expect to receive from my perceived [State Pension age] to my actual [State Pension age]’. Ms W said she lost approximately £45,000 due to not reaching her State Pension age until six years later than expected.

344. Since these losses flow directly from changes in the law, rather than from how those changes were communicated, they are not losses resulting from maladministration. We would not recommend remedies for any losses that do not result from the maladministration.

349 Our approach to considering financial loss draws a distinction between direct financial loss and cases where maladministration leads to the loss of an opportunity to make different choices, where that lost opportunity might have financial consequences. ‘Our guidance on financial remedy’ gives examples of injustices that we do not think amount to direct financial loss. These include ‘loss of a significant financial opportunity’, such as the loss of an opportunity to go to university or develop a career.

This distinction removes all claims for loss of pension funds.

In a PHSO report entitled Trusting in the Pensions Promise, March 2006 which concerned loss of pension rights due to changes to private sector final salary occupational pension schemes (approved by DWP) the Ombudsman found three elements of maladministration.

5.164. I have made three findings of maladministration, namely:

- (i) that official information – about the security that members of final salary occupational pension schemes could expect from the MFR [minimum funding requirement] provided by the bodies under investigation – was sometimes inaccurate, often incomplete, largely inconsistent and therefore potentially misleading, and that this constituted maladministration;

- (ii) that the response by DWP to the actuarial profession’s recommendation that disclosure should be made to pension scheme members of the risks of wind-up – in the light of the fact that scheme members and member-nominated trustees did not know the risks to their accrued pension rights – constituted maladministration; and

- (iii) that the decision in 2002 by DWP to approve a change to the MFR basis was taken with maladministration.

At the time of the 1995 legislation, which affected women born in the 1950’s, there was no evidence of an impact review and certainly no mitigating plans were put in place to prevent women from falling into destitution. Unfortunately, looking at whether that decision had been taken with maladministration has not been considered as part of the PHSO remit, despite a very lengthy investigation process.

Alternatively, the March 2006 report into private pensions accepts that maladministration led to direct financial loss which should be repaid via public funds.

6.15. I recommend that the Government should consider whether it should make arrangements for the restoration of the core pension and non-core benefits promised to all those whom I have identified above are fully covered by my recommendations – by whichever means is most appropriate, including if necessary by payment from public funds, to replace the full amount lost by those individuals.

The contrast with the findings of the 2006 report was brought to the attention of PHSO during the consultation process only to be dismissed with the statement that their approach to considering claims of direct financial loss had changed.

Wide discretion allows the Ombudsman to set his own standards, to alter those standards at any time and to withstand legal challenge to the standards applied as confirmed in the stage one report.

- We have discretion to decide how to investigate complaints and to decide what test to apply when making decisions about maladministration. The 2015 judgment says:

‘It is for the Ombudsman to decide and explain what standard he or she is going to apply in determining whether there was maladministration, whether there was a failure to adhere to that standard, and what the consequences are; that standard will not be interfered with by a court unless it reflects an

unreasonable approach. However, the court will interfere if the Ombudsman fails to apply the standard that they say they are applying.’

Under the new standards, 1950’s women couldn’t claim that lack of information caused them direct financial loss as outlined in the final report.

355. We do not consider any loss that is dependent on the choices someone would have made if the maladministration had not happened is direct financial loss. This is because there are intervening events between the maladministration happening and the loss being experienced – the choices the person makes, the actions they take and the results those actions have. The choices people make also involve a balance of benefits and disadvantages. For example, somebody who does not work and instead spends time at home with family may experience the disadvantage of not earning money, but has the benefit of being with or caring for their family, or the other options that having additional time might bring.

This will come as a significant blow to many women hoping for a substantial payout due to financial loss. The final report confirms that the identified maladministration did not lead to direct financial loss for any of the six test cases.

357. We consider it is at best very unlikely that the maladministration could have led to the sort of direct financial loss envisaged in our guidance in any case. The delay in DWP writing to women about that Act did not cause direct financial loss in the sense that we use the term in the sample complainants’ cases, and we find it difficult to see how it could have done so for others.

362 The sample complainants told us they lost out financially because they made decisions they would not have made if they had known, or known earlier, that their State Pension age had changed. Even if the sample complainants would have made different choices, any financial loss resulting from the choices they made is not direct financial loss. Their loss would flow primarily from the choices they made, for which DWP is not directly responsible or accountable.

Having dismissed direct financial loss, PHSO agrees that delays in complaint handling caused ‘stress and anxiety’ and then determines that the primary injustice was ‘loss of opportunity’.

459 For most sample complainants we consider the primary injustice is that they were denied opportunities to make informed decisions about some things, and to do some things differently, because of maladministration in DWP’s communication about State Pension age. That is a material injustice.

Finally, PHSO proposes a remedy for the stress and anxiety suffered and for the lost opportunities. Given that all of the women were approaching retirement, and the fact that PHSO determined that the maladministration didn’t occur until 2006, their opportunities were limited by their age, caring duties and ill health.

489 We have explained our thinking about where on our severity of injustice scale the sample complainants’ injustice sits. We would have recommended they are paid compensation at level 4 of the scale.

Level 4 (£1,000 to £2,950): a significant and/or lasting injustice that has, to some extent, affected someone’s ability to live a relatively normal life. The injustice will go beyond ‘ordinary’ distress or inconvenience, except where this has been for a very prolonged period of time. The failure could be expected to have some lasting impact on the person affected. The matter may ‘take over’ their life to some extent.

Annex C

As the DWP has refused to acknowledge the maladministration the Ombudsman has no option but to lay the report before parliament.

How much power does Parliament have?

Parliament is largely made up of back-bench MPs and select committees. The government (executive) holds all the power as we can see by these repeated calls from PACAC for reform of the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman, which are duly ignored, year after year. Here is the latest plea from the 2022/23 Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman scrutiny session.

We renew our call for legislative reform of the PHSO, the principle of which enjoys widespread support among stakeholders and the ombudsmen that would be directly affected. The PHSO have outlined to us some concrete examples of the operational issues that are being caused, and exacerbated over time, by the lack of reform. Reforms are long overdue, and we do not agree with the Government that this is not an urgent issue; rather it has been neglected too long and further delay is no longer tenable. The

Government should reconsider its position on reforms and set out its plans, ahead of the general election. It should consult with a wide variety of stakeholders, including different ombudsmen, parliamentarians and PHSO service users. All political parties should include a commitment to reforming the legislation relating to the PHSO in their upcoming manifestos ahead of the next General Election, coupled with a commitment to introduce such legislation early in the next Parliament.

There will now be much foot-dragging on the part of the Government, as seen in the Post Office Horizon scandal and it will be difficult for any committee or concerned MP to put forward a financial remedy that goes beyond the sum suggested by the Ombudsman.

What have we learned from this long-awaited report?

- The Ombudsman has no powers of compliance.

- The Ombudsman must rely upon Parliament to put pressure on the executive.

- The Ombudsman can select his own standards and alter those standards as he sees fit.

- The Ombudsman can use his own definitions to determine ‘maladministration’ ‘harm’ and ‘injustice’.

- The Ombudsman can take whatever time necessary to complete his investigation.

- If the complainant disagrees with the report they are forced to take legal action in the form of judicial review to challenge the decision.

- If the body under investigation disagrees with the report they can simply refuse to carry out the recommendations.

- This is what accountability looks like.

Footnote: On 18 December the Labour government announced that they would not be paying out any compensation to the 1950’s (Waspi) women. Justifying this decision with the following statement;

“90% of those impacted knew about the changes that were taking place”.

The government has for some time been batting away MP questions on this issue by saying they were carefully considering the Ombudsman report. Well, they clearly missed this statement on the first page of the report.

2. Research reported in 2004 showed that only 43% of all women affected by the 1995 Pensions Act knew their State Pension was 65, or between 60 and 65. The research report said it was ‘essential’ that particular groups, including ‘women who would be affected by the change’, should be ‘appropriately targeted with accessible information on the equalisation of [State Pension

age]’.

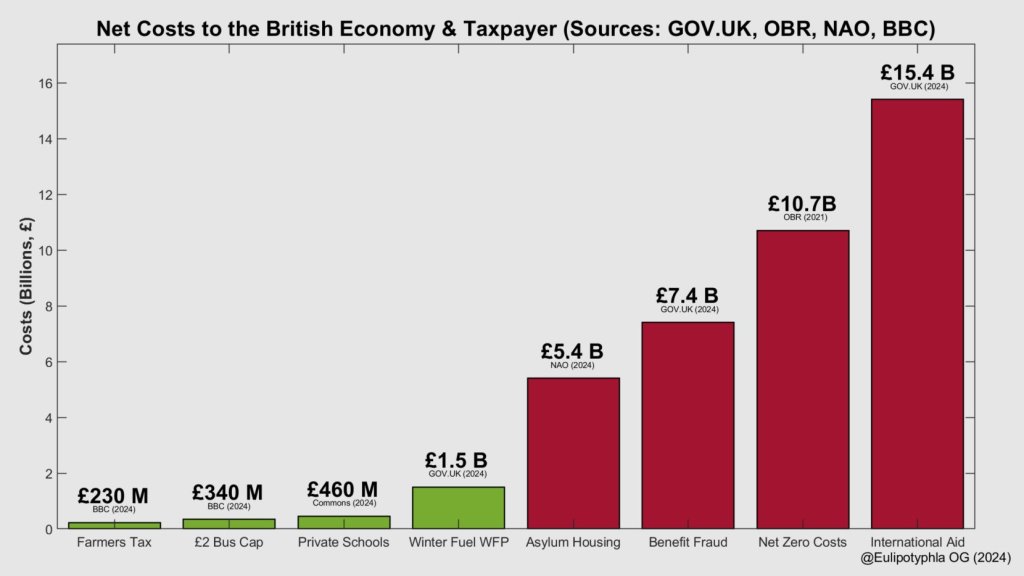

90% appears to be a completely fabricated figure, alongside the £22 billion black hole that is continually used to squeeze more money from the public. The chart below shows that the fairly insignificant gains of the budget are quickly swallowed up by a largely international spending agenda. Against this background will Waspi women continue to be left out in the cold?

well I guess we all knew how his report would be worded, Mel Stride was probably looking over his shoulder when he wrote it!!!

LikeLike

A marvellous investigative blog Della. I don’t suppose too many people are aware of the 2006 Ombudsman decision in which maladministration regarding private pensions schemes was found by Ombudsman, along similar grounds to the WASPI claimed maladministration, and recommendations made for financial redress. It’s shocking that the Ombudsman is able to change his own standards without having to justify his decision. If anyone needed proof that Ombudsmen are in the pocket of the government then this is it. It’s quite clear that the DWP engaged in maladministration right from the start but the Ombudsman has used the most weaselly arguments imaginable to wriggle out of his responsibility to help the public and has succeeded. I suppose the fact that all parties involved know that the WASPI women are not going to riot and tear the place up so they can be dismissed and sidelined without any great worry. A very sad situation.

LikeLike

Another example of the infamous “corrupt by design”

LikeLike

Its all a complete sham. How much public money is spent on the PHSO who has no powers, no competence, who makes it up as they go along and is unaccountable? Just part of the system designed to protect and line the pockets of a few while putting on a game of charades to everyone else.

In my own case, the PHSO obtained independent expert evidence that supported my complaint against the NHS and they drafted a report in my favour. But then, suddenly, when the Trust’s CEO heard of this outcome, who was mates with the PHSO’s MD, they colluded to destroy the original report and produce a new one that ignored all the evidence and didn’t uphold my complaint. Its all cronyism and corruption in this grubby country:

https://patientcomplaintdhcftdotcom.wordpress.com/

LikeLike

Reads like one of their clinical negligence ‘investigations/reports’. 😄

LikeLike

Damage limitation is their motto

LikeLike