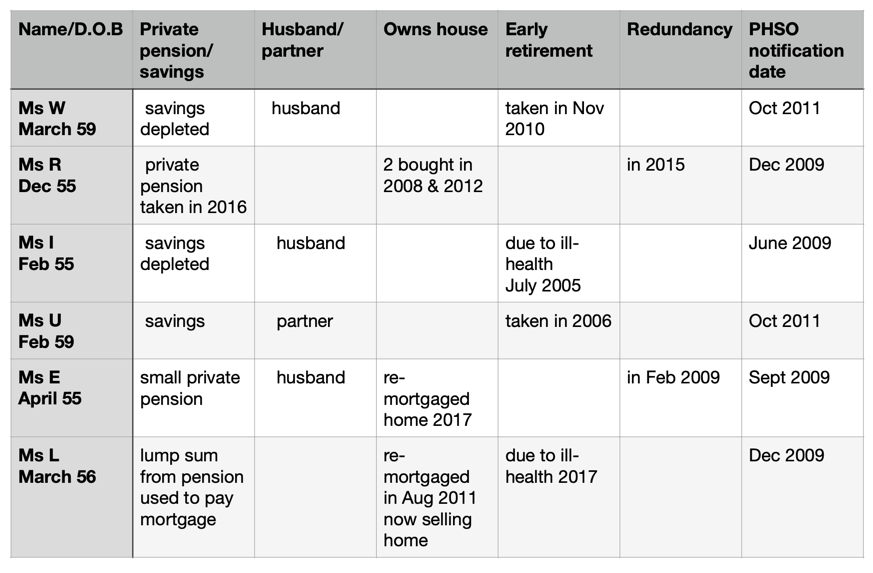

Once PHSO released their final report on March 21st 2024, it was finally possible for the 1950s women to see the six sample cases which were used to represent the whole 3.6 million cohort. The chart below shows key information taken from the PHSO report.

The age spread is only 4 years with three of the six born in 1955. All of the six commented on using savings or private pensions to bridge the gap. Four of the six were listed as having partners to share household costs. In the other two cases, there was no mention of relationship status. Three of the six owned their own homes and could remortgage or sell to improve their financial situation. Four of the six took early retirement, while the other two were made redundant and would presumably have received a redundancy payment. In four of the cases, the women finished work before the date they should have received notification if the DWP had communicated without maladministration (final column). The report therefore concludes, that the maladministration ‘made no difference’. Nearly all of the women stopped working before turning 60 with one retiring at 61.

Not represented:

- Women who were paying rent and had no property assets to fall back on.

- Women who had to continue working past 60, despite ill-health

- Women who had to retire early due to ill health but had neither a partner nor a private pension to fall back on

- Divorced women who took a financial settlement that ended 6 years before their pension kicked in.

How were the 6 test cases selected?

The Ombudsman intervened in November 2017 but the six sample cases were not announced until nearly a year later, in October 2018. This article from the Financial Times (2017) reveals some interesting information about the selection process.

According to Jamie Potter, partner at Bindmans, Waspi will be “working to assist the ICE in identifying an appropriate representative sample, with a view to establishing whether there was maladministration and how any such maladministration should be addressed”.

Ms Beevers said that Waspi’s legal team will be selecting the sample cases in two categories: women only affected by the 1995 Pension Act, and women affected by that act plus the 2011 one.

HTTPS://WWW.FTADVISER.COM/PENSIONS/2017/11/29/OMBUDSMAN-INTERVENES-IN-WASPI-COMPLAINT-CASES/

Did the WASPI campaign team and ICE select a representative sample?

On the day the final report was published, David Hencke from Westminster Confidential put up a blog post critical of the WASPI campaign and in particular the role of Angela Madden, Finance Director and Chair of WASPI.

50s women are back to Square One after the Parliamentary Ombudsman “cops out” of awarding them a penny

The following comment was made by ladymuck01.

Is there any evidence to support the view that the WASPI campaign was actually working against the women successfully achieving compensation?

We know that they, or at least their legal team from Bindmans sat around the table with representatives from ICE and had plenty of time to look through the complaint files. The Ombudsman report gives the following information (emphasis added).

168. Between July and August 2016, each sample complainant complained to DWP that they had not been given adequate notice that their State Pension age was increasing. Five of the six used a template letter

This suggests that at least five of the chosen complainants were guided by the WASPI campaign group in the initial stages.

175. The template response DWP sent the sample complainants in August 2016 included an explanation of the legislation, what had prompted it, and the steps DWP had taken to communicate the changes. It referred to 2006 and 2012 survey results about awareness of State Pension age. It explained that the issues had been fully debated in Parliament, and no further changes or concessions were planned. Any challenge to the policy of State Pension equalisation would need to go through ‘statutory appeals channels or the courts’.

This appears to be a fork in the road. Were the women complaining about the policy and possibly the way the policy decisions were made in 1995, or were they only complaining about the lack of notification? At this point, it would seem that all six sample cases were guided in their response by the WASPI campaign group.

176. The complainants all wrote back to DWP later that month, using a template letter tailored to their personal circumstances. They stressed they were not complaining about the policy but about how the change to State Pension age had been communicated, and the impact a lack of notice had had on them. They also said DWP’s complaint responses contained inaccurate or irrelevant information, and had not addressed their concerns. Some said responses had been sent late.

Given what we know now, was this a lost opportunity to challenge the actual legislation itself through the statutory appeals channels? Challenge the failure to carry out an impact review, the failure to agree on mitigating provisions for women falling into destitution and the failure to make a legally binding obligation on the DWP to give sufficient notice to plan ahead, a stated intention of the White Paper 1993.

27. The White Paper stated:

‘In developing its proposals for implementing the change the Government has paid particular attention to the need to give people enough time to plan ahead and to phase the change in gradually.’

‘The change will not begin to be implemented until 2010. The lead-in period of over 16 years allows plenty of time for people to adjust their plans.’

The report also confirms that one of the six sample cases was the ‘lead case’ which had previously been investigated by ICE, presumably finding no maladministration, as the conclusions from this complaint were used to dismiss further cases. Was this a sensible option?

186. ICE told us it received ‘an unprecedented volume’ of complaints about DWP’s communication about State Pension age, and it received no additional resources to deal with them. It said the vast majority of complainants used a standard template. ICE selected a ‘lead case’ (one of our sample complainant’s complaints) for investigation and then applied its findings in that case to each of the cases it investigated. It found there was no requirement for DWP to inform women of changes to their State Pension age, and that DWP had no standards for communicating changes about State Pension.

There is also evidence that the women were encouraged to take their complaints to the Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman at the earliest opportunity, rather than continue to negotiate with either DWP or ICE for a more favourable outcome.

200. DWP told us the campaign group that published online template complaint letters encouraged women to progress their complaints to the next stage of the complaints process as soon as they received a response. It considers the campaign group’s aim was for complaints to progress to us [phso], regardless of the quality of DWP’s responses.

We can all see now that the Ombudsman has no powers of compliance, a notoriously low uphold rate and tight restrictions on compensation payments. This must have been known to the WASPI team given they were receiving advice from Bindmans.

Was it always a trap?

The whole WASPI case stinks of corruption at every level. The 6 so called ‘representative cases’ was a farce and why were WASPI directors involved in selecting cases and conveniently liaising with the Ombudsman and ICE and goodness knows who else behind the scenes and meanwhile the gullible women all thinking it was above board? 6 cases cannot possibly in any way ever be representative of millions of women. Also any complaint case going to Ombudsman should be completely private and confidential between the complainant and PHSO. Surely Ombudsman was breaking his own rules in the process of discussing 6 representative cases. So that is a failing of due process in itself isn’t it? Other big and pressing questions are why were the WASPI women being fielded into a dead end of the PHSO system in the first place? Who orchestrated all this? Certainly Bindman’s were happy to see it sent to PHSO and were conveniently ‘helping’ with template letters to DWP early on in the complaint process. Where did all the money go for the crowdfunding to take this to a Court of Law? And now it is urged by the Ombudsman that Parliament may need to step in when the DWP refuse to accept the failing. But Parliament is not supreme or has sovereignty over the people, it is the people that put them there in the first place surely?

Sadly, the majority of WASPI women are still believing they will get their just compensation. They are being urged to write to their MPs – as if that will do any good! All just a distraction and no doubt one that will be used in the General Election campaign with wild promises to women. Fact is that the WASPI women have been done over well and truly and they had better wake up fast. Many lost well over £48,000 and even if they did get some compensation – the amount Ombudsman is recommending is breadcrumbs, knowing full well that few would even get the breadcrumbs and no doubt find themselves yet again in a lengthy process to prove how the loss of the pension affected them. These women have already paid a lot of money in taking up their cases with DWP and ICE and vast amounts of their time and effort.

And it seems the so called ‘Government Watchdog PACAC has kindly written to the Secretary of Sate for Work and Pensions, Mel Stride to ask for an update following the Ombudsman report. How nice when we all know the role of PACAC. Just all another lot of theatre.

LikeLike

A most accurate summary. It has been a stitch up all the way through. The best line of attack may have been a JR on whether the decision to equalise was taken without maladministration. A failure to provide a risk assessment was a significant aspect to focus on.

LikeLike

UIN 21313, tabled on 12 April 2024

Charlotte Nichols

‘To ask the Secretary of State for Work and Pensions, if he will provide compensation to women who have been affected by changes to the State Pension age.’

Paul Maynard

‘In laying the report before Parliament at the end of March, the Ombudsman has brought matters to the attention of this House, and a further update to the House will be provided once the report’s findings have been fully considered.’

https://questions-statements.parliament.uk/written-questions/detail/2024-04-12/21313

LikeLike

In due course is the phrase they use. Don’t hold your breath ladies.

LikeLike

House of Commons:

Brendan O’Hara MP

‘Despite how the Minister might wish to spin it, the ombudsman’s report was absolutely damning, totally vindicating the WASPI women and their campaign…The vehicle is there, Minister. Will the Government now work with my hon. Friend [Alan Brown] and support his private Member’s Bill, so we can bring this matter to a conclusion as swiftly as possible?’

Ian Blackford MP

‘Can we imagine what would happen in this place if it was announced that private sector pensions were being put back by six years? Rightly, there would be outrage, and there should be outrage about what happened to the WASPI women.’

Grahame Morris MP

‘The Secretary of State says that there are 200,000 fewer pensioners in poverty, but 270,000 WASPI women have died waiting for justice. How many more will die before he finally comes along and implements those recommendations in full?’

Mike Amesbury MP

‘This interim statement felt like a non-statement. It spoke about clarity but offered none at all to WASPI women or Members of the House. I repeat what many across the Chamber have said: on what day and in what month can we expect a full statement? WASPI women up and down the country expect that full statement.’

John McDonnell MP

‘Members of this House share the same feelings as the ombudsman and the WASPI women: we have no confidence in the Department for Work and Pensions to resolve its basic failure of decades ago.’

Imran Hussain MP

‘Will he [Mel Stride] at least accept that every time a Minister stands up and says “undue delay” or “due process” they really mean that they have no intention of addressing the problem, and are saving face and kicking the can down the road?’

Jim Shannon MP

‘Does the Secretary of State agree with my constituent’s suggestion that the Government agree urgently to pay a reasonable lump sum, followed by an increase in their pension payments until the deficit is recouped, thereby making it easier to balance the public purse?’

https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2024-03-25/debates/D0F6412D-D924-4029-84E7-6E4D69E848A3/Women%E2%80%99SStatePensionAge?highlight=waspi#contribution-FC18079E-CF3E-4900-8A14-A25EFF1C1C8B

State Pension Age (Compensation) Bill Private Members’ Bill (under the Ten Minute Rule)

Originated in the House of Commons, Session 2023-24

Last updated: 8 February 2024 at 11:28

https://bills.parliament.uk/bills/3683

LikeLike

No matter how representative the six cases were they could never represent those pensioners who couldn’t complain – those who relied on food banks and died.

LikeLike

Very true. Some women had nothing to fall back on.

LikeLike

It would be interesting to know the criteria for selecting the representative complainants. Did the WASPI representatives have full access to all the complaints or were they just given a summary? The PHSO legislation states that complaints are private and cannot be shared. Also, what criteria were used to choose the complaints. It is extremely strange that all the complaints appear to have involved relatively “well off” women when it is obvious that the women who would have suffered the most would have been less well, as you suggest. Perhaps only middle class women complained to the Ombudsman. But it certainly seems highly suspicious, although everything about the way that the Ombudsman operates is highly suspicious.

LikeLike

These test cases came via DWP and ICE so had already been examined before arriving at PHSO. I’m sure all 6 suffered loss and harm as a result of the pension increase. But given only 6 would be selected there should have been greater diversity with regard to circumstances. Did the selection process make it easy for phso to determine no direct financial loss and was that deliberate?

LikeLike

You stated above ”Three of the six owned their own homes and could remortgage or sell to improve their financial situation.” – That is an assumption you have made and which is not entirely factual due to the wide differences at play within the UK. Supply and demand for property varies particularly when the local Industries are decimated and lending decisions for potential buyers determined by Banks/Building Societies soley cherry picking those buyers with only cast iron full time work in buouyant Industries. Mortgages are a noose around all peoples necks. Are we back to blaming 50s women for the choices they had made as thats what your article infers. Many women could not offload their homes as easily as you seem to think. No woman whether renting or buying should be carrying the can for extensive maladministration and the discrimination foisted upon them. Women at PHSO test and malads were informed that the test cases were representative of the 650 complaints, in Jan 2018 and not the dates your using above and that implies that the data the women held and the problems encountered were of the same or a similar nature. Conversely 3 women that you have charted above may or may not have rented. Its totally immaterial. All women unless wealthy ie those that had been advised by IFAs of the 1995 Act have been affected and its not any 50s womens place surely to subsidise a corrupt and rogue Govt. by implying ‘worst affected’ or ‘means testing’ or Intergenerational Fairness Jargon. We cant have 3.8m women in the dock and so to pretend otherwise is futile. There are women and men going into print who are ‘keyboard warriors’ with absolutely no input into the PHSO their MPs or the APPG all now pushing their own individual cases, yet have been absent for the last 9 years. Are we to await another 9 yrs till some of them manage to put pen to paper? On a more general note only the original Waspi and original Bindmans + PHSO can identify why some cases were identified as test cases. Good luck with that as 50’s women incl majority of test cases have been excluded big time and wholesale from determining the actual processes used by all three to determine test cases or otherwise, with PHSO attending meetings with Waspi which again excluded test and other affected malads. Your long association watching the PHSO will tell you they are shrouded in secrecy and delays and thats the same nonsense employed here

LikeLike

Understanding of the wider issue seems to be absent here. In the 1960’s Quintin Hogg, for the then conservative opposition, described the Ombudsman legislation as it went through parliament as ‘a swiz’ and the conservatives opposed it. In 1993, when in government, the conservatives extended ‘the swiz’ to include complaints regarding the NHS.

Close scrutiny of the legislation reveals that the Ombudsman has total autonomy regarding whether he chooses to investigate anything and also how he does it. He has no power of enforcement. There have been many instances over the years where his recommendations have just been ignored. This suits the main political parties very well.

The essence of this blog is correct. The process of selecting the six specimen cases was flawed and, as any self respecting statistician will tell you, six is such a small sample out of 3.5 million as to be irrelevant when it comes to identifying any trend in the level of harm caused.

I would urge the anonymous author to join efforts to bring about change so that the NHS and Government Departments, particularly those on the merry-go-round of high office, are properly held accountable and have no place to hide. The reality is an injustice has been done to many and proper restoration is unlikely given the law governing the Ombudsman’s powers.

LikeLike

Good overview David. I would like to reiterate that there is no blame attached to the 6 sample cases. They put forward their concerns in good faith and had no role in the selection process. They were also forbidden from contacting each other.

LikeLike

Sorry you have made unwarranted and incorrect assumptions about what you think 50’s women could or couldnt do when they were hit with an additional 6 years. Much as in the same way that the PHSO deals with their ‘victims’ and their skewed probability theory. Whether women had bought or rented is not the issue – Each women youve presented here above has her own private hell and had made her own plans for retirement usually well before any letter may or may not have popped through her letterbox. Women in Aberdeen presented complaints where their properties were in some cases being re-possessed, were made redundant and couldnt meet the mortgage and the 6 yr heist had kicked in. Others renting but able to get benefits to keep a roof over their heads – Others had to go and live with younger siblings and leave the area completely. There was no help afforded women in Scotland by our own Parliament here and ‘Intergenerational Fairness’ and ‘Inclusion’ being the buzz words but ONLY if you were not an older women – A brief overview on Twitter shows 50’s women how they are despised by some younger gens who have swallowed this hook line and sinker, particularly if they cant get on the housing ladder. Where you are very correct is that there are only a few selective paragraphs written about each test complainant because the bulk of the dross is designed to not only exonerate the DWP but BLAME all women irrespective if they are or were home owners or renting, your falling into the same trap. Theres been absolutely no Impact assessment done by the DWP/ICE/PHSO – Women have a month to appeal the PHSOs report so hope that you will put your points in if you feel so strongly about his selection of representative cases.

LikeLike

There is no blame here for the women in the test cases. There is only the question as to whether they collectively represent the full effect of the pension change across the board.

LikeLike

Some points to consider re your chart – House prices in Aberdeen for example fell from 2015 to date so neither re-sale nor rent an option and women on contract are in general within the UK not usually entitled to any redundancy. Furthermore when Industries are hit world wide and redundancies are the name of the game you are assuming women in their 60’s can easily find work, this was not the case in Aberdeen – a one horse town. What work some 50s women could pick up here was seasonal at Xmas as eg meeters and greeters in M+S and were rewarded with cracked ribs and broken legs when shop pavements not de-iced. The DWP notification dates youve used are incorrect too but have been applied by the PHSO in their haste to exonerate the DWP from liability eg stage 1. – I dont think taking a pop at test complainants who have carried the burden is a smart move. All women at malad PHSO final stage have been silenced due to the PHSOs confidentiality clauses and am sure they did not pick years of unwarrented intrusion and tireless effort into producing accurate timelines to be picked off in blogs or posts making assumptions. What is certain is that women who paid into the original waspi c/fund were left ‘high and dry’ when Bindmans left due to the toxicity in that campaign – The 650 plus women at final stage have largely had to DIY and only 2 test complainants are waspi women. The SERPS people affected by DWP maladministration were successful in their pension quest at previous PHSO. However the stats in general I agree are very poor.https://www.aberdeenlive.news/news/aberdeen-news/aberdonians-over-45000-worse-because-9048782

LikeLike

This was not an attack on individual women at all. There is very little detail in the report on the 6 sample cases and none regarding their location. All women suffered a financial loss and many were totally unprepared. The point of the piece was to ask the question about full representation. Is it possible to represent millions of women with 6 cases and did the spread of cases demonstrate the full severity felt during the long wait for pension payments?

LikeLike