Since Rob Behrens became the Ombudsman in April 2017 he has been at great lengths to stress the importance of ‘impartiality’. In his pre-appointment hearing with PACAC (18.1.17) he confirmed that ‘impartiality’ was central to the role of the Ombudsman.

Once the ombudsman loses impartiality, he or she ceases to be an ombudsman and ceases to be independent. There always has to be that test, but you need to know that the ombudsman service has done as much as it can, and we have to explain that we are not the consumer champion but that we are an independent ombudsman service that has to adjudicate on the basis of the evidence that is available. Q 14

On the subject of evidence available, what evidence is there that the Ombudsman acts in an impartial manner when resolving complaints about government bodies and the NHS? There is absolutely no evidence to support this claim as there is no external scrutiny of the Ombudsman process, no external scrutiny of Ombudsman reports and the only body charged with any kind of external scrutiny – the Public Administration and Constitutional Affairs Committee (PACAC) chaired by Sir Bernard Jenkin have chosen not to scrutinise individual complaints. FOI request

What evidence is there that the Ombudsman is not impartial?

Quite a lot.

- There is the fact that PHSO is Parliament’s Ombudsman, set up by legislation agreed in the House as a body to hold government departments, Ministers, MPs and civil servants to account. An inherent conflict of interests from the beginning. The Parliamentary Commissioner (PCA) later known as the Ombudsman was set up as an officer of Parliament designed to assist MPs in holding the executive to account via public complaint.

The PCA cannot be seen as independent of, and therefore is linked inexorably with, Parliament. In fact it would seem to be difficult to separate the PCA from Parliament without significant statutory changes. Denning Law

- This report from Paul Burgess 1983 found that the Ombudsman did all in his power to accommodate the body under scrutiny, whilst ignoring the complainant and confirmed that a lack of external scrutiny had allowed the Ombudsman to be taken into the ‘bosom of the establishment’. Not an easy place to be if you are claiming to be impartial.

- More recently the Patients Association (PA) wrote a number of damning reports about the work of the Ombudsman. In 2015 (following the publication of a previous report) over 200 people contacted PA to state their dissatisfaction with the Ombudsman service. The PA collated their responses in a report entitled Labyrinth of Bureaucracy where 66% stated that the final Ombudsman report was factually incorrect, inconsistent or substandard and 62% said that the Ombudsman overlooked evidence which contradicted the NHS Trust apparently siding with the Trust. Lack of impartiality was a repeated complaint.

- Review request data indicates dissatisfaction with the Ombudsman investigation process and decision making. In 2017-18 complainants made 1,724 review requests. By contrast, only 17 review requests were made by public bodies. So for every 100 review requests made by complainants, only 1 review request was made by a public body. FOI request

This discrepancy is in keeping with a very low uphold rate. In 2017/18 only 2.6% of accepted formal complaints were upheld in full and only 12.2% were given partial uphold. The vast majority of people who complain to the Ombudsman go away with nothing.

- Consumer feedback data is used by PHSO to demonstrate to PACAC the level of public confidence and satisfaction in the service. If the Ombudsman acted without impartiality then this should be highlighted in low consumer scores. In July 2016 PHSO changed their method for gathering consumer data and now compare external complainant feedback with an internal score generated by the Ombudsman as part of their Service Charter. They seek the complainants’ feedback on all key areas apart from Q10 which relates to the impartiality of the service. This omission has been criticised in the PACAC Annual Scrutiny Report 2016/17.

Impartiality and unconscious bias

47. The one commitment the PHSO’s service charter does not ask for complainants’ views on is number ten: “We will evaluate the information we’ve gathered and make an impartial decision on your complaint”.76 Many written submissions suggested that the PHSO’s investigators are biased towards professionals or the body being investigated, called ‘bodies in jurisdiction’ by the PHSO.77 In evidence Amanda Campbell told us, “I have exactly the same said to me from bodies in jurisdiction; they believe that we are biased towards complainants.”78

If the number of review requests is taken into account (as given above) it can been seen that for every dissatisfied body in jurisdiction there are 100 dissatisfied complainants so it would appear to be something of a glib response from Amanda Campbell CEO given the importance of impartiality to the very DNA of the Ombudsman service.

As public confidence relied upon the fact that the Ombudsman was seen to be impartial, PACAC requested that PHSO asked this question of complainants and published it as part of their service charter in the future. Although PHSO agreed to find a way forward on this by 2017/18 they were still not publishing on the specific question which dealt with impartiality. Consequently, Dr Rupa Huq a member of PACAC asked the following question in January 2019.

Last year the Committee recommended that as part of the service charter you ask complainants about whether they perceive you as impartial in your decision-making. How and when do you intend to do that? Oral evidence Q111

She was given a waffly response from Amanda Cambell CEO which suggested that securing this information was difficult but all they need to do is put Q10 of the Service Charter to the public as it is stated; We will evaluate the information we’ve gathered and make an impartial decision on your complaint. Why is PHSO so reluctant to put their ‘impartiality’ to the test?

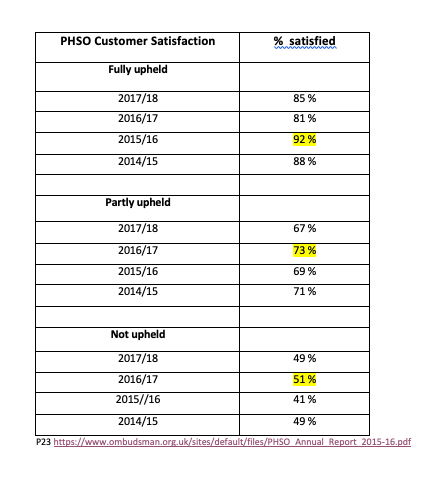

- Customer satisfaction data should act as a barometer of performance giving valuable feedback to both PHSO and PACAC. It is however, difficult to have any confidence in this data when the percentage scores fail to reflect the external criticism of this organisation. It has now been widely accepted that between 2012 and 2016, under the stewardship of Dame Julie Mellor, the Ombudsman service had ‘lost its way’.

“When I joined, it was an organisation in transition, which was not performing well. It wasn’t clear what its core role was anymore. My aim was to create an organisation that reflects the Ombudsman DNA – meaning being independent of bodies in jurisdictions, but also of complainants.”Interview with Rob Behrens June 2018

Yet the satisfaction scores under Dame Julie Mellor’s were higher than they are now under Mr Behrens leadership. Why didn’t these ‘independently gathered’ scores reflect the levels of dissatisfaction cited by the Patients Association, reported to PACAC by the public in numerous written accounts and now acknowledge by PHSO themselves?

In 2017 Martin Lewis and Money Saving Expert (MSE) carried out an independent survey of Ombudsman services. Approximately 100 people responded regarding PHSO and 82% said their experience was poor (p 54) with 75% saying they felt that PHSO was biased in favour of the other party (p 59) MSE-2017 These ‘independently gathered’ low-score figures are also replicated on other free-access consumer forums such as Google reviews and Trustpilot. Why is there such a disparity in scores?

If the PHSO customer satisfaction scores are an indicator of public confidence they are an unreliable one but as no other indicator exists, these are the scores which are repeatedly used to demonstrate approval. It can be seen that there has been no real movement over time but a rather static stodge of data.

- Most recently Sir Liam Donaldson used these scores to determine that there was a level of customer satisfaction in the Ombudsman service. It would appear that he was not availed of this view from any other sources. Unusually, he had been able to take a peek behind the curtain of the secretive PHSO investigation process. Following an upheld judicial review against PHSO, Sir Liam was recruited as an independent expert to review the way PHSO used clinical advice in determining the outcome of investigations. His Clinical Advice Review was completed in December 2018 but not released until March 2019, after the annual PACAC scrutiny session which was held in January. Referring to the court judgement, Sir Liam cites the fact that the ‘internal’ world of PHSO where caseworkers remained convinced of the validity of their actions, clashed with the ‘external’ world where those actions were held to be perverse and illogical to the point of illegality. This goes to the very heart of ‘self-regulation’ and warns that PHSO should not be able to continually monitor its own performance without some form of external scrutiny. With direct access to caseworkers, clinical advisors and complainants Sir Liam had a rare opportunity to examine the whole investigation process. Although measured, his report reveals a system which is rife with opportunities for bias from the pre-determination of lay caseworkers who sift clinical evidence to present their preferred account, to the failure to provide all the evidence to the clinical advisors or allow them to give valuable input which goes beyond the narrow question base procedure and emphasised the failure to involve the complainant, often a key witness, until the process was complete.

- With access to written transcripts, case studies, investigation reports and the attendance at a ’round table’ focus group meeting with twelve complainants, Sir Liam reported that the complainants told a consistent story and one which needs to be heard.

It would be wrong to simply note the critical comments and conclude that they were an unrepresentative minority. The sources of information on complainants’ experience provide rich and important insights into the functioning of the PHSO service. It was particularly striking that the group of complainants, with whom I, and the Clinical Advice Review Team, met, was not made up of vexatious or unreasonable people. They expressed frustration and, anger, but the problems that they described with the handling of their complaints should be a vital source of learning. Many of their criticisms of the PHSO’s processes, and those in the documented accounts and submissions, were consistent with what I had already observed, having read a sample of records provided to me. (p13)

Why would Sir Liam even consider that the views from complainants would be from an ‘unrepresentative minority’ who were ‘vexatious’ or ‘unreasonable people’? Where did that idea come from? Quite possibly from the Ombudsman himself who continually describes critics of his service in this disparaging manner. Here is Rob Behrens discussing the ‘user voice’ in a recent article written for ‘Research Handbook for the Ombudsman (p463)

Reading Sir Liam’s Clinical Advice Review it is obvious that there is no ‘clear and accessible policy framework’ and certainly not one which protects the public. There is also a great deal of evidence, as cited above, that the Ombudsman is not impartial, hence the dissatisfied users joining together. The fact that James Titcombe had to fight PHSO with ‘tenacity and resilience’ speaks volumes about the service he received. But let us ponder upon the full meaning of this statement for a moment and consider just who is claiming ownership of the ‘higher moral standing’ here.

The PHSO definitely is not impartial after taking three and a half years to reach them via a corrupt and covering up Valuation Office Agency complaints system the PHSO simply retreated doing nothing . More about this story of corruption, extortion complicity and abuse to the public in February 2021

LikeLike

Look forward to hearing more.

LikeLike

If the Ombudsman began being impartial tomorrow it would open the floodgates for reinvestigation demands that they would not be able to handle, and would be very embarrassing to deal with. How much evidence is needed? It has been ignored for year on year and nothing changed for those who discovered the prejudice and bias after the PHSO portcullis had been drawn down and the bridge raised. The PHSO operated Boris-like tactics well before that Tory leader discovered that we have laws to designed to protect against sleaze, prejudice and discrimination. The PHSO is on shaky footing and I am sure will be proven as illegally operating well after vital lessons were dismissed as ‘beyond complainants’ expectations’ to resolve.

LikeLike

PS: Dennis (above) I was destroyed waiting over 8 years for a “final report” – still full of errors, evidence ignored, and contrived ‘evidence’ from a key witness involved in the negligence (name withheld) who not only reinterpreted the Coroner’s verdict for his own devices, but also put new words into the Coroner’s mouth as he would have liked to have heard. No specialist experts were consulted and NICE Guidelines for Best Practice were dismissed as irrelevant by untrained and inept caseworkers (names withheld). Appealing again, and two years later, RBehrens found it impossible to answer leading questions on JMellor’s continuation of persecutory and dismissive culture at PHSO, and the result was just more offensive complainant denunciation on a ‘fake’ PHSO Review which was never put on record; or was redacted, which is actually worse!

LikeLike

Rob Behrens is the man who doth protest too much. Is he being disingenuous? Maybe he thinks that if he keeps repeating the same message (even though I don’t believe him) that people will believe him or else he is repeating the same message so often he believes what he says when evidence is the opposite. Not a man to be trusted. It is noticeable how so many people at the top of various organisations all have the same characteristics as do many of their subordinates. I believe that subordinates are the fall people who are appointed and by their incompetence make the top dog look good. That is what happens in NHS Management aka Peter’s principle.

LikeLike

A complete sham. I waited 15 months for the final report – full of errors, evidence ignored, apart from a single medical expert report that was also full of errors, no other witnesses even spoke to. I asked for a review with dozen of pages of factual evidence, highlighted medical notes, four signed witness statements, all ignored. Unbelievably useless organization.

LikeLike

Useless by design Dennis. Has been for years.

LikeLike

Dennis, everything you say mirrors my experience, many others too. We all have been through this ‘managed process’, and I use the term managed in it’s most sinister of forms.

LikeLike

How sly that PHSO waited until well after PACAC to release the clinical advice review. Seriously, it’s incredible they are behaving this way. Mind you, the disrespect PACAC treats the public submissions with, by ignoring them totally year on year maybe it wouldn’t have made any difference anyway. What is the external feedback PHSO obtained? Do you mean by a market survey organisation on their behalf? They would still be writing the questions they want asked and as we know the service charter misses out the most needed questions of all, not only about bias. So what with deliberately delayed publishing of the clinical advice review and not providing the answer regarding Q10 on bias, they are now brazenly and arrogantly withholding evidence and stage-managing events to cover-up the truth. Much like they do with investigations really. #patternofbehaviour

Behrens almost vicious attack in his “user voice” section speaks volumes. People have valid concerns and the fact that he doesn’t address them, but instead uses well-worn tactics to attempt to discredit people, tells us everything we need to know.

LikeLike

Even the words “These users need to be reminded…” are laden with the disdainful arrogance that so many of us have experienced at the hands of the PHSO.

And as for suggesting that “the complaint is their own”, that’s exactly the issue. Once the PHSO has distorted a complaint, stripped it out, and been wilfully selective in what is investigated, it is no longer the complaint the user recognises as their own.

Yes, as EJ comments in the last paragraph, the “almost vicious attack” from Mr Behrens speaks volumes and tells us everything we need to know.

LikeLike

Arrogance verging on divinity possible because Mr Behrens knows there is no mechanism to hold him to account.

LikeLike

Another great blog! If Rob Behrens feels he has a “higher moral standing” than the rest of us then why would he sit on a critical report for 3 months while the PACAC scrutiny was ongoing and then very quietly publish it without any notification? Doesn’t seem to me like the behaviour of someone with “higher moral standing”.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Spot on.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It seems from this latest report, that Mr. Behrens is even more arrogant and evasive than his predecessors .

LikeLiked by 1 person

I fear so!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Value for money is mandatory at audit of public service. When will taxpayers have confidence that its public servants comply with this mandate? will PHSO ever present some evidence of ANY VfM? Its track record suggest PHSO will never be of any value to the taxpayer. Why is it still in existence? How can the NHS improve with PHSO blocking all evidence?

LikeLike

The NHS doesn’t improve. Sir Liam made that clear in the start of his report. We are paying to be closed down.

LikeLiked by 1 person

What I have come to learn since I got involved with the complaint handling system, from 2011 onward, is that no amount of common sense or indeed evidence is ever taken into consideration by the PHSO. The hierarchy within the NHS is shaming the hard work nurses and doctors do in increasingly difficult times. The cover up starts at the very top of the NHS and is carried forward to the bogus Health Ombudsman where the level of corruption is so breath taking that it leaves victims of poor health care service even more vulnerable than before. (And after the life changing events we suffer that’s no mean feat, which proves beyond a shadow of doubt this corruption is absolutely deliberate).

LikeLiked by 1 person

We have establsihed that the so-called investigation service (PHSO and the rest) are specifically appearance-based to perpetuate a general illusion that there is some regulatory powers in place, which there are for the government’s spin machine of which RB is the latest mouthpiece of deflection. Our pressure group and other concerns continue to publicly flag up the illusion with the truth towards reversal.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Substantiated truth Peggy not spin.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent article, ‘facts’ should not be ignored. Rob Behrens has been in post now for nearly two years. As yet no proof that he is not all words and no positive action. Unless something happens soon have to draw the conclusion the whole set up is a total sham. Terrible waste of public money, with no accountability for supposedly public servants. We the public are being taken for an expensive ride.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well said Jill –

RE: Public Purse

Rob Behrens is on £192,000 to do what exactly?

What is Amanda Campbell’s wage?

How much money is being spent on blocking a Victim’s basic Civil Right to justice?

How many Academics across the UK are being employed to write misleading reports and collude in the propaganda that things are “going well” with the Ombudsman?

But here’s the issue about the “Truth” behind the workings of the PHSO;

Della has volunteered her time into trying to understand why the Ombudsman is a “chocolate teapot”.

Who’s Facts are reliable and trustworthy?

The data provided by Della, a Volunteer, who has worked tirelessly for others or someone employed by the Ombudsman to tow the line?

Thank god for yours and Della’s voluntary work.

Many thanks F

LikeLiked by 3 people

Money is a key issue Fiona. Money funds research. Academics may wish to explore other issues with the Ombudsman but who funds the project?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well said FW facts are what Della deals in just a shame we seem to have guesstimatesm from PHSO. How can he continue to deny this

LikeLiked by 1 person

Arent we just…its appalling!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Is the PHSO impartial? He is, like everyone else on the State payroll, a Quisling, concerned only about keeping his seat on the Gravy Train. . Norman Scarth. WW2 veteran. ________________________________

LikeLiked by 2 people

You are right Norman. Rob Behrens can only serve one master and it is clear he doesn’t beleve he is there to serve the public.

LikeLiked by 2 people

In a word “NO!”

LikeLiked by 1 person

The PHSO ombudsman is as impartial as Brexit is straightforward

LikeLiked by 2 people

Well said

LikeLiked by 1 person